“Graduate students have stories to tell about their teaching. What experience do you think is most important to share with other graduate students and professors? How have you come to think about teaching as you do? What are the most meaningful teaching activities, accomplishments, barriers, and outcomes for you?”

Those are the opening lines from the Jan 2016 call for proposals for what became Teaching as if Learning Matters: Pedagogies of Becoming by Next-Generation Faculty (abbreviated TAILM hereafter), published in 2022. I have previously written a little bit about the book, in that blog about how it is a memorial to my 18 years of pedagogical work with an academic institution. I felt motivated to write this post because I’ve been invited to share the origin story of this book with graduate students participating in a cross-institution book group. I wanted people outside that book group to have access to some of that conversation and the “why” of this book.

Yep, it took seven years for the book to emerge from concept to object in our hands. For readers interested in what transpired in those seven years, here’s an overview of that timeline:

- Summer 2015 – conversations and ideation with co-editors

- Jan 2016 – prospective contributor meeting

- Summer 2016 – full draft chapters due

- Summer 2017 – final version chapters due

- Fall 2017 – prospectus and sample chapters sent to potential publishers

- Fall 2018 – proposal accepted with an academic publisher for peer review

- Fall 2019 – reviews and suggested edits received

- Spring 2020 – revised manuscript submitted to publisher

- June 2020 – publisher board approved publication

- Jan 2021 – final files sent to publisher

- June 2022 – book in print

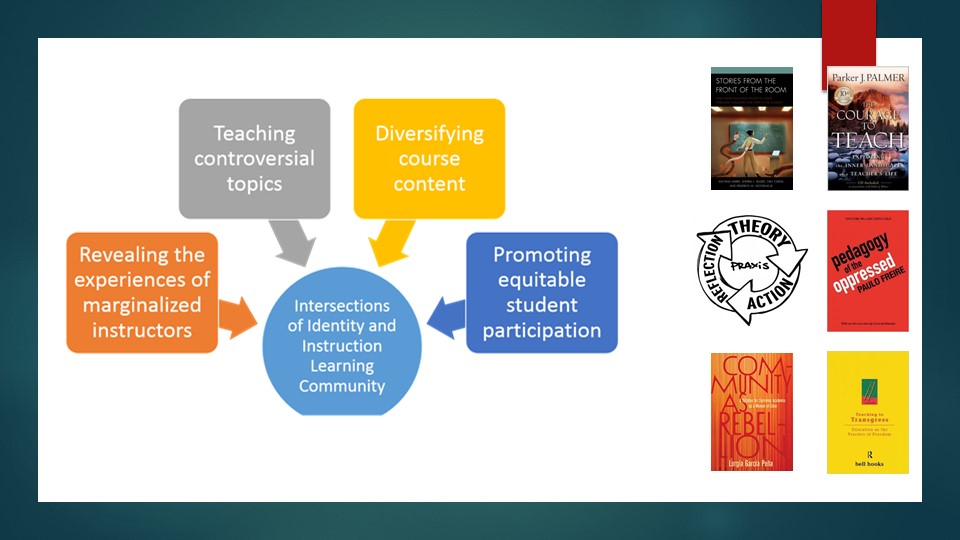

In fact, one seed for the book had been planted in my mind in late fall 2014 when two Black women graduate students who regularly worked with me in the teaching center approached me with hard truths. The work we did in the teaching center didn’t speak to their experiences in the classroom and the challenges to authority they regularly faced. The “best practices” we shared in workshops were based on studies of the averaged experience for the students in the class to be practiced by people with assumed authority in the classroom, instructors who fit the default cultural expectation of who belongs at the front of the room. Rarely did our best practices consider the experiences of the instructors, and especially instructors of marginalized, “othered” identities such as gender, race, nationality, age, and institutional role. What emerged from that conversation was a semester-long co-created learning community created with, by, and for graduate students who faced identity-based challenges to authority in their classrooms.

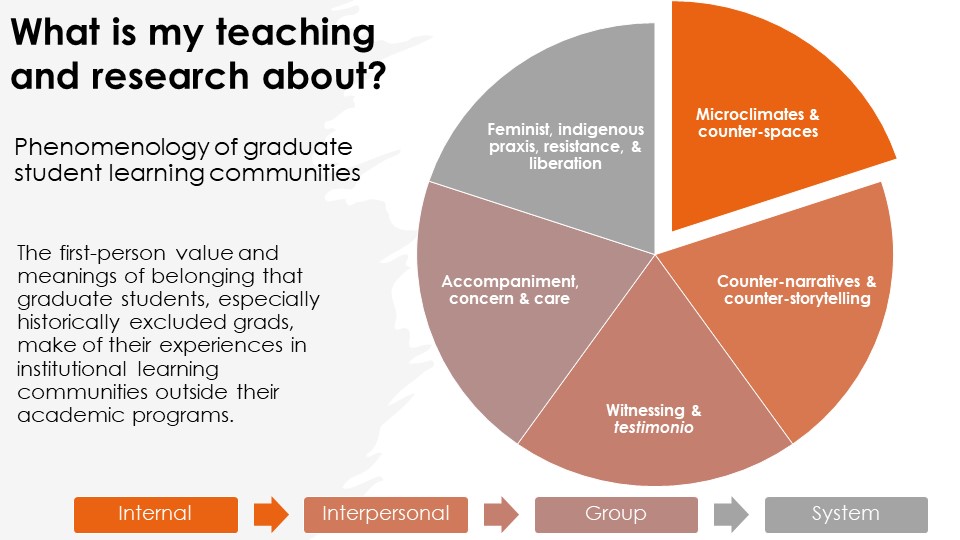

A second seed for the book was planted in noticing what made that learning community (LC) different from other LCs I had previously facilitated. It wasn’t an expert-to-novices dissemination of teaching tips and it wasn’t a support group of project-based classroom interventions. It was a community of praxis that was co-created by all the members. We drew upon practices in witness and testimonio; counter-narratives and counter-storytelling; accompaniment, concern, and care; micro-climates and counter-spaces of belonging, affirmation, and empowerment; opportunities for reflection, construction of new narratives, and meaning-making; and resistance and liberation principles. We explored together the embodied experience of teachers of marginalized identities, important questions about teacher identity and integrity, and how much of their authentic selves instructors feel they can safely bring to the classroom. Our readings came from faculty speaking in the first person about identity-related experiences in the classroom: for example, hooks’ Teaching to Transgress, Harris et al.’s Stories from the Front of the Room, Ahmed’s On Being Included.

A third seed for the TAILM book was planted in noticing a gap in readings to support our conversations. What literature there was about graduate student instructor identity development was written ABOUT graduate students, “objective,” observed from the outside, and studied by more empowered and resourced others who determined the research questions and what was important to highlight about the subjects of study. It’s just the way research is generally done about graduate students. I had conducted similar research studies ABOUT graduate students for 10 years. Literature TO graduate students was generally written as advice by highly experienced faculty offering their silver bullets to teaching. Just do this and that to be successful and effective: McKeachie’s Teaching Tips, Bain’s What the Best College Teachers Do, Calarco’s Field Guide to Grad School. To be clear, I don’t think there was ever willful malintent and I think these resources have an important place and offer lots of extraordinarily valuable wisdom.

At least three seeds started a new garden for me in graduate student development: who is at the center (marginalized graduate students), what is at the center (the embodied experience of becoming a teacher), how things are centered (how we talk with each other, what we talk about, what we read, what kind of knowledge is privileged). Being part of that learning community in 2015 fundamentally changed how I am part of the scholarly community in graduate student development. I try to use my role and access privilege to let graduate students decide what was important to say about their experiences and journeys to becoming teachers. I try to relinquish control and sole authority on deciding on the important questions. I try to make spaces for graduate students to speak publicly about the questions they think are important, the dilemmas they face and dreams they pursue, the disillusionment and reconstitution processes they undergo, and how they understand their developmental paths to integrating personal and professional identities.

I planted those seeds in the summer of 2015 after co-facilitating that learning community. The formal idea for the book started when I reached out to three women colleagues in graduate student pedagogy. I believed they shared the vision of a book by and for graduate students about their process and paths of becoming educators. I knew the project was too big to take on myself and I knew they each had skills and access that would facilitate the project. I had worked with each of these women since 2005 in separate capacities for most of the time I was employed at the university teaching center. Working on the book collaboratively (for seven years) was a culmination of all the previous projects, workshops, classes, learning communities, and research projects we had worked on. In the meantime, the four of us have continued to collaborate on other research projects about faculty-taught graduate courses in college pedagogy (one of which I’m now teaching!). The book keeps bearing fruit as contributing authors and editors share the book through invited talks with graduate students and graduate student developers.